Charles Bukowski died with the ignominy of knowing he’d spent his most intellectually fertile years working as a post office clerk. It is also true that Charles Bukowski was a sullen dipsomaniac, a terrible misogynist, a bitter depressive, and an emotionally itinerant cynic who never really broke out of the Los Angeles underground scene, and hated himself for it.

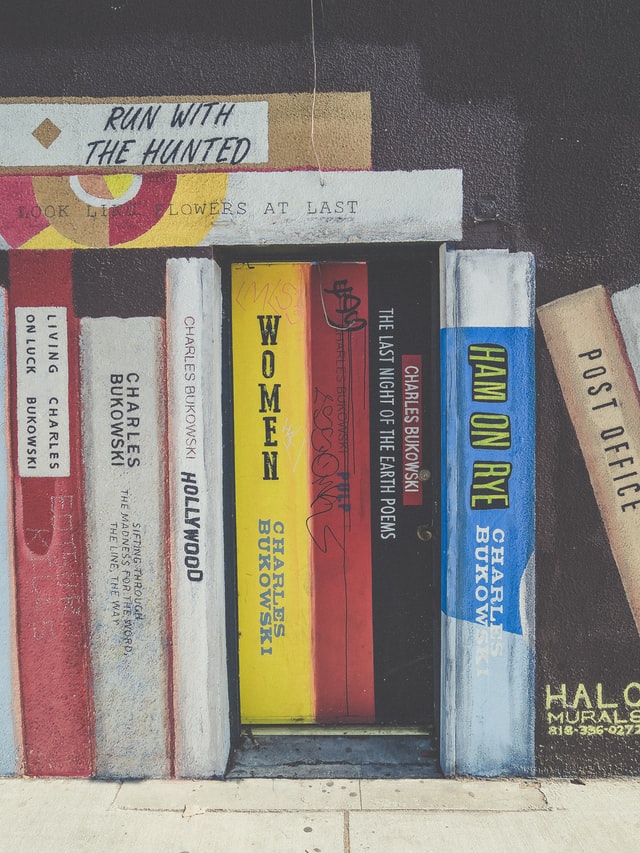

(Photo by JOSHUA COLEMAN on Unsplash)

Charles Bukowski’s contemporaries weren’t too much better; Kerouac drank himself to death. Burroughs was a heroin addict who murdered his wife during a spur of the moment ‘William Tell’ act in a bar full of people. Ginsberg was convinced he’d met Walt Whitman in a supermarket.

These are sad creatures, and sad creatures tell stories of loneliness and isolation and long, barren American roads, of jalopies and jazz and jungles of thousands and thousands of disenchanted yokels searching for something, anything- for that feeling of ‘IT’ no one had ever properly articulated to them, because no one was quite sure what ‘IT’ was. Some would argue that these stories are not stories of 21st century living. I’d be inclined to agree. And we might ask ourselves if they still matter.

The answer can be found on the gravestone of one Heinrich Karl Bukowski, a small-town German immigrant from a broken home, lumbered with a pock-marked face and an addiction to alcohol:

“DON’T TRY.”

Questionable advice from a man who spent his best years driving a postal wagon. And yet, you know, and I know, it’s about more than just that. Because Charles Bukowski’s legend was built on his uncompromising truth, and his own belief that, if nothing else, he had earned the right to tell his story on his own terms. And never is that more needed than today.

The beauty of Charles Bukowski was that he wasn’t afraid to be ugly; he didn’t write about his six month holiday to the Bahamas or having a ten million dollar turnover by the age of 25 (solely via the slippery medium of #graftingforsuccess). He wrote about finding the will to get up in the morning, about learning to breathe, about taking each day as it comes.

He wrote about living in a time where the only way to creativity was through unabashed authenticity, to accept your shortcomings and know that just to ‘be’ was enough. In an age where impostor syndrome is rife and the overqualified and under-confident fear being discovered as unworthy of success, the motto of Bukowski and his literary contemporaries is resoundingly clear; own your story, warts and all.

What, then, can we learn from the Beat Generation?

That being organically you is liberating?

That the capacity to believe in yourself can be freeing for both you and those you interact with?

That forcing the hand of fate never wins?

Perhaps. But if “DON’T TRY” is the theory, then total, unwavering self-belief is the practice. And if Charles Bukowski and his friends are anything to go by, it’s this conviction that allows you to begin crafting the narratives that surround you- it’s only when you are totally comfortable with yourself that you can start to own your story, not just passively watch it occur. The longer you sit and wait to establish what you cannot do based upon what others can, is the moment in which that résumé, be it figurative or literal, ceases to be a record of achievement but a millstone of self-doubt around your neck.

It’s all too easy to fade into the background, to convince yourself that a failure or shortcoming is indicative of a greater problem, that officials all over the world are sniggering by the water-cooler at the philistine who erroneously presumed he or she was right for the job. The answer is simple: Be More Charles Bukowski. Let your story find its own form. Tell of your mistakes. Trust in the process of ‘being’. Know that there’s always tomorrow. Try again. Tell others about this struggle. Beat naysayers at their own game. In this auto-Instagram age, imperfection is ammunition. If you don’t make it a weapon in your arsenal, it sure as hell will be in somebody else’s. Charles Bukowski knew this. That’s what gave him his power.

The Beat Generation made storytelling their business. And if freedom is money, owning their stories, their truths and their tragedies made them very, very rich men. Because there can be no greater liberation than learning to live.

Author: Anna Hanlon

Interested in the Own your Story program? Please drop us a line